Do You Understand Your Industry

Legends of Marketing Series by Gary Hoover

Do You Understand Your Industry?

I have spent the last several years advising perhaps a thousand entrepreneurs and corporate executives on how to develop their strategies and grow their business. These enterprises include every size from startups to billion-dollar corporations, every industry from high tech to restaurants, and every location from small town Texas to Malaysia and Mexico. One of the most common things blocking people’s strategic thinking is a failure to understand their own industry and those industries and companies that bear on the enterprise’s success.

There is no way one can understand the potential of their company or plot a great strategy without understanding their industry and how their company fits in.

The first step is to understand the big picture. Start with these questions:

- How big is the industry? This information is readily available in the United States at Census.gov and by simple googling, typing in that question.

- How fast is the industry growing? (From the same sources)

- What is the industry trade association? Go deep on their website, which often contain tons of information. Subscribe to their newsletters and read their publications. Learn the industry jargon and see what worries or excites industry participants. Some industries have multiple and state or regional associations.

- What are the industry trade publications? Most trade magazines also have great websites. These provide a wealth of information. Most issue newsletters, often free.

- What are the key industry trade shows? Attend them! Talk to everyone. (I usually talk to the editors of the trade publications, as they know more about industry trends than anyone, and few others bother to talk to them.)

The second step is to understand the industry structure:

- What are the steps in the “value chain,” from raw materials to the end-consumer?

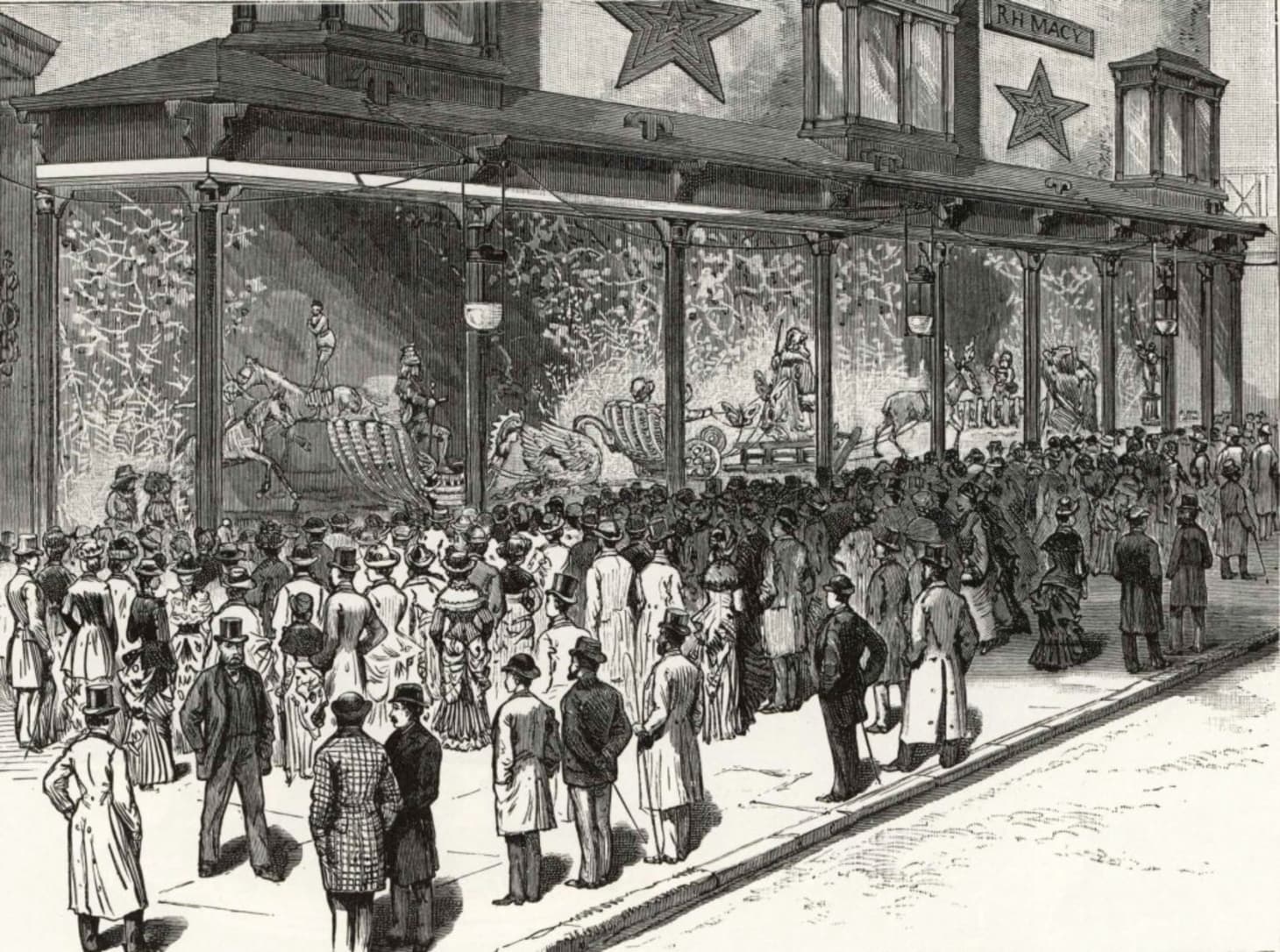

- At each step – manufacturing, wholesaling and distribution, retailing or ultimate delivery – is the industry fragmented or consolidated? Are there hundreds of players or is the business dominated by just a few participants? Each industry is unique in this regard. It is not uncommon to find that there are a few giant players coupled with many much smaller ones. In lodging, retailing, restaurants, and other industries, are the individual locations company-owned or franchised to independent owners? In hospitals, education, and some other industries, there is a mix of non-profit and for-profit enterprises. All these factors matter.

- What is the nature of the distribution system and channels? For example, books are sold to bookstores both directly by publishers and by big wholesalers like the Ingram Book Company. On the other hand, libraries may work with different systems and have different wholesalers. In some industries, manufacturers’ representatives (who do not hold inventory) may dominate; in other industries, wholesalers or distributors (who hold inventory in stock) are the key. Because the giant wholesaling system is hidden from the sight of consumers, it is often the most overlooked part of the process. The US restaurant industry could not function without giant distributors like Sysco, yet few restaurant customers (diners) have ever heard of the company. Might your company do business with such wholesalers as Anixter, Avnet, Arrow Electronics, Ingram Micro, ABC Supply, WW Grainger, C&S Wholesale, McKesson, Cardinal Health, Graybar, Univar, or Ferguson Industries?

Third, learn everything you can about the major participants at each level of the system:

- Who are your competitors? Take a broad view of the competition. Executives of Carnival Cruise Lines once told me their main competition was not other cruise lines, but it was Disney World. Museums compete with amusement parks and movie theaters for the consumers’ dollar.

- Who are your suppliers?

- Who are your customers, at each level – distributors, wholesalers, retailers, end-consumers? You cannot know too much about your customers, how your products or services fit into their lives or their business processes.

Fourth, go deep on each company you discover:

- Is it a public or private company? The easiest ways to find out are: a) look at their Wikipedia page and see if it says “private” or shows a stock listing; or b) type into Google “____(Company Name)____ Investor Relations.” If it takes you to an investor relations page, it is a public company, one in which anyone can buy stock. If there is no Google result on “investor relations,” you have a private company, the wrong name, or a division of a larger company. Public companies publish all their financial data, including gross and net profit margins, revenues, and varying levels of data on their sales and profits by division or product line. The most important document to read is their Annual Report, called a 10-k form by the Securities and Exchange Commission. Public companies also provide PowerPoints and other presentations on the company’s strategy, where it is growing, what it wants to expand what it wants to sell. Devour this information. It is much harder to discover information on private companies – local business journal publications and Crunchbase are often good sources of information.

- Where is the company headquartered?

- What is the background of its leaders? Are they finance people or marketing people or technologists?

- How big is it? Is it growing? How profitable is it? What are their goals? What are their other divisions and activities? Is the part of the company you deal with their main business, a side show, a money-loser, or a cash cow?

These steps may sound like a lot of work, but the future of your company and the intelligence of your strategies and tactics depend on “knowing the game.” These steps should not be delegated: even if you have help doing the digging (hire a firm like Bizologie or make the process a student project), leadership must internalize what is learned. No one other than top management can imagine (and execute) the possibilities for your enterprise!

Gary Hoover is a serial entrepreneur. He and his friends founded of the first book superstore chain Bookstop (purchased by Barnes & Noble) and the business information company that became Hoovers.com (bought by Dun & Bradstreet). Gary served as the first Entrepreneur-in-Residence at the University of Texas at Austin’s McCombs School of Business. He has been a business enthusiast and historian since he began subscribing to Fortune Magazine at the age of 12, in 1963. His books, posts, and videos can be found online, especially at www.hooversworld.com. He lives in Flatonia, Texas, with his 57,000-book personal library.

Gary Hoover is a serial entrepreneur. He and his friends founded of the first book superstore chain Bookstop (purchased by Barnes & Noble) and the business information company that became Hoovers.com (bought by Dun & Bradstreet). Gary served as the first Entrepreneur-in-Residence at the University of Texas at Austin’s McCombs School of Business. He has been a business enthusiast and historian since he began subscribing to Fortune Magazine at the age of 12, in 1963. His books, posts, and videos can be found online, especially at www.hooversworld.com. He lives in Flatonia, Texas, with his 57,000-book personal library.

To get updated information about the team at Apogee Results, please follow us on your favorite social media channels.