Legends of Marketing Series by Gary Hoover

Splashing Outside the Digital Box

Those customers may spend record amounts of time on their smartphones, tablets, and laptop screens, but they also still live most of their lives in a real, three-dimensional, non-digital, non-virtual world. They walk, bike, or drive streets, they visit bricks-and-mortar stores for 90% of their spending, they go to concerts, festivals, churches, schools, dinners, and parties. Above all else, they talk to their friends about products, services, and what is in the news, what is cool.

And in this world of competition for attention and engagement, those smartphones and other devices are distinctly flat and two-dimensional, no matter how imaginative you may be in their use. We all recently witnessed the record sales day of Cyber Monday 2018. But even Cyber Monday is flat, the same old thing, essentially boring. Its excitement is entirely price-driven, not exactly how you build a unique and durable brand. Cyber Monday is not about customer experience or engagement.

In this environment, how does one make a splash? Perhaps we can get some inspiration from the “splash-makers” of the past. Perhaps there are opportunities to make a splash in the three-dimensional world, even for online-based marketers.

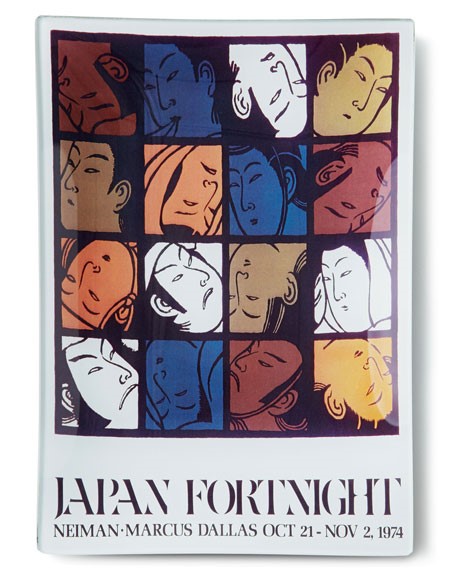

“Mr. Stanley” Marcus was the man most responsible for making Neiman Marcus a globally known luxury brand, even though during his years as company chief, they only had stores in one state, Texas. He explained to his publicists that every media outlet received hundreds of corporate press releases each day, most going unread and into the trash. He said the only press releases his company wanted to send out were items that were truly news, that would be worthy of making the front page. His specific tactics included a Christmas catalog which included such items and “his and hers aircraft” and in-store two-week-long “fortnights” which celebrated the culture, art, and fashion of a different country each year. These attracted international attention. Today the company generates about 100 times the revenue that it did when Mr. Stanley built its reputation for fashion innovation.

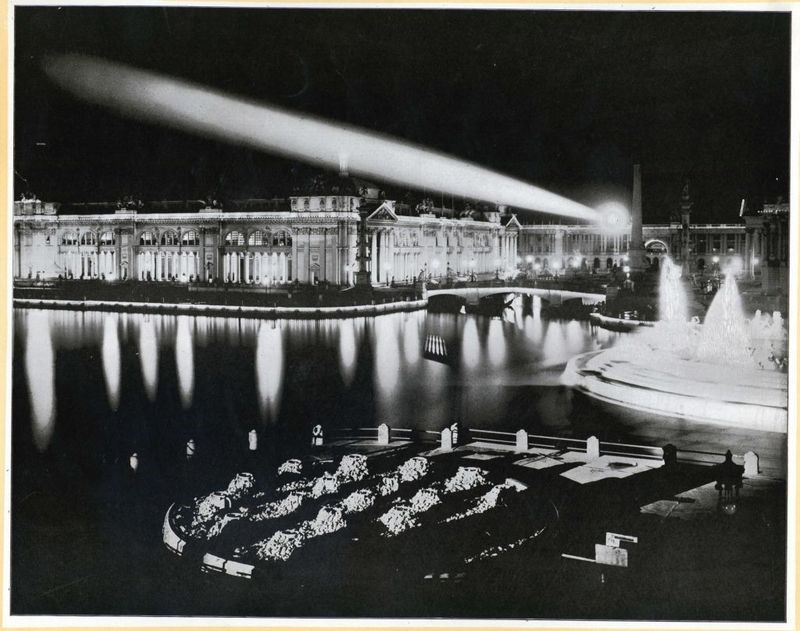

H. J. Heinz built one of the most recognizable global consumer brands. At the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition (World’s Fair) in Chicago, he had a display booth, but it was relegated to an upper level gallery that was rarely visited. So he dropped coupons across the fairgrounds, offering a gift to anyone who came by his booth. The gift was a small pickle lapel pin; the result was that the fair authorities had to reinforce the floor of the upstairs gallery due to the heavy foot traffic. At the close of the fair, the other upstairs exhibitors gave him an award because of all the attention he brought to them. In 1898, Heinz bought the big Ocean Pier along the popular Atlantic City Boardwalk, where he held concerts, art shows, and demonstrated Heinz products. Operating for 46 years, the Heinz Pier drew 15,000 people a day in the peak summer season. His competitors were left in the dust – and not just in Atlantic City!

At the same Chicago World’s Fair where Heinz passed out pickles, George Westinghouse substantially underbid larger and better-known competitor Thomas Edison’s General Electric to power the Fair’s remarkable and unprecedented lighting system. The Westinghouse name soon became a household word.

A few years later, Westinghouse also got the contract for the giant turbines to power the Niagara Falls Power Plant, one of the largest in the world.

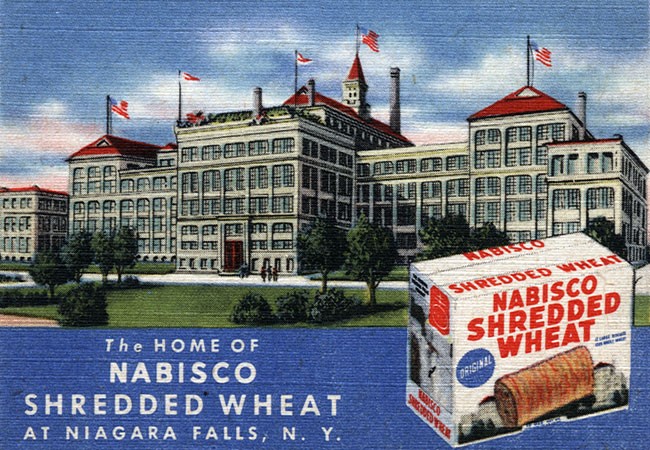

From 1901 until discontinued sometime around 1946, tours of the shredded wheat factory were part of the marketing of Niagara Falls. Honeymooners saw the falls and then toured the factory. The company estimated that around 100,000 visitors took the tour annually. Perky had designed the factory with balconies and aisles that permitted visitors to see the machinery in operation. They were welcomed every day of the week all year except Sundays, in the lobby above, fitted to resemble that of a hotel. Off to one side was a demonstration area where free lunches were served to visitors that used shredded wheat products in various ways. Tour guides led the visitors through the 5.5 acre factory and up to the roof garden and auditorium where they heard lectures on diet, cooking and good living.

When radio (“wireless”) came along a few years later, John Wanamaker’s New York department store put a radio receiving office on the top floor, to draw attention and publicity to the store. Young radio operator David Sarnoff was the first to hear of the 1912 sinking of the Titanic, gaining Sarnoff (and Wanamaker’s) attention and fame.

None of these promotional ideas were the norm, none were expected. Competitors were shocked, and often thought the ideas stupid. Bold ideas require imagination and courage, thinking “outside the box.”

These stories may seem old and irrelevant, but surely there are modern parallels that imaginative marketers could develop. In more recent years, we’ve seen Red Bull gain global attention with unusual sports and events, and Richard Branson spread the Virgin brand by attempting unrivaled flights.

- Is there an opportunity for your company to leverage concerts, fairs, events, marathons, or festivals, especially in geographical areas where you have a lot of customers?

- Is there a way to reach out to your ever-moving customers, whether that be through wrapping some cars (or trucks or scooters) with your logo? Or running a tour bus across America, stopping in key cities across the way to demonstrate your products?

- What can your company or brand do that no one else is thinking about? What would really make a splash? Even if it requires leaving the comfortable world of the flat screen where your competitors are stuck.

Gary Hoover is a serial entrepreneur. He and his friends founded of the first book superstore chain Bookstop (purchased by Barnes & Noble) and the business information company that became Hoovers.com (bought by Dun & Bradstreet). Gary served as the first Entrepreneur-in-Residence at the University of Texas at Austin’s McCombs School of Business. He has been a business enthusiast and historian since he began subscribing to Fortune Magazine at the age of 12, in 1963. His books, posts, and videos can be found online, especially at www.hooversworld.com. He lives in Flatonia, Texas, with his 57,000-book personal library.

Gary Hoover is a serial entrepreneur. He and his friends founded of the first book superstore chain Bookstop (purchased by Barnes & Noble) and the business information company that became Hoovers.com (bought by Dun & Bradstreet). Gary served as the first Entrepreneur-in-Residence at the University of Texas at Austin’s McCombs School of Business. He has been a business enthusiast and historian since he began subscribing to Fortune Magazine at the age of 12, in 1963. His books, posts, and videos can be found online, especially at www.hooversworld.com. He lives in Flatonia, Texas, with his 57,000-book personal library.

To get updated information about the team at Apogee Results, please follow us on your favorite social media channels.